Vaughn Matthews

Invasive non-native species

What is an invasive non-native species (INNS)?

Invasive non-native species (INNS) can be any organism! It can be a plant, animal, fungus or algae that is not indigenous or native to a particular area. They can cause great environmental and economic harm to the area by upsetting the natural balance.

INNS are usually introduced by human means for economic gain, or by accident through international transport. They may also be a result of climate change.

Controlled under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, Section 14. Included species are listed under Schedule 9. It is illegal to introduce, or allow to spread these species into the wild. Many are still sold for domestic planting.

Gillian Day

Features of invasive species

Be sure not to confuse INNS with exotic or ornamental plants. There are many species that are not native to the UK that have become naturalised and do not pose a threat to our native ecosystems. See INNS features below:

- Not adapted to our ecosystem and can therefore exploit niches that other less competitive species once held.

- Excel in ecosystems that are already in decline from other pressures.

- Hardy, highly adaptable species.

- No natural predators.

- Resistant to native illnesses (or)

- Bring infections from overseas that native species are not resistant to.

- Grow in ways that are incongruous with our native habitats – often dominating.

- Occupy sensitive habitats and reduce diversity by changing conditions.

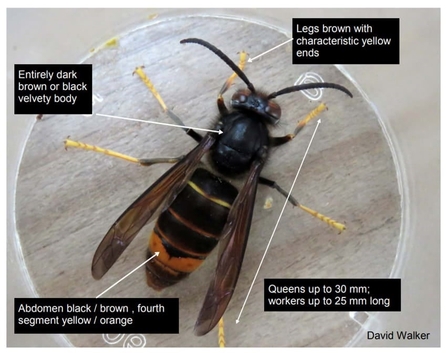

David Walker

Identifying an invasive species

When identifying an invasive species, an identification app can help. Experience and ID practice also goes a long way. If it was established in the wild, you can check if it is listed in Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981). There are also emerging invasives (such as the Asian Hornet), which are not yet listed.

If you see a species doesn't look right or you suspect that it is an invasive non-native species, the following questions are helpful:

- Are they evergreen in a deciduous woodland?

- Are they numerous?

- Are they 'taking over' a habitat quickly and resulting in decreased biodiversity?

Amie Cook

Steps to take

So what do you do if you see what you suspect might be an invasive non-native species in an area? We recommend the following steps...

- Identify correctly. Ecological knowledge and experience goes a long way here. Or you can use an app to identify the species, such as PlantNet or iNaturalist.

-

Research the management of species.

-

Report the sighting to INNS Mapper and a local action group.

-

Take action yourself. Remember to wear gloves and speak to a local action group, or google for advice if unsure.

Focus on common species

Vaughn Matthews

Himalayan Balsam

Impatiens glandulifera

When? Starts to emerge April/May, grows up to 3m, flowers in June and sets seed in September.

Where? Partial shade, riparian (riverside), wet soils, woodlands. Wide tolerance range.

Why? Introduced in 1839 for gardens, quickly spread, now naturalised. Huge ecological impact, lesser economic impacts.

Management advice

•Pulling up stems

•Always crush!

•Cutting back before seeding (Balsam Bashing in May and August)

Report sightings?

Yes, worth reporting. Helps inform local taskforces.

ADVICE: Stop balsam bashing when there are green seed heads and the cusp of seed heads have become ripe. Sometimes this is mid-end August, depending on the weather conditions that summer. The Team Wilder Community Ecologist recommends leaving any remaining balsam until next year after this has happened.

The best window is to get them when they’re flowering because once they’ve gone to seed the seeds are really resilient, and event killing the plant with immature seeds can still result in seeds ripening on the ground. Ideally, all bashing should cease by the time the flowers have mostly gone over.

WildNet - Philip Precey

Japanese Knotweed

Fallopia japonica a.k.a Reynoutria japonica

When? Late spring emerges from soil rhizomes rapidly growing canes, flower in late summer. Doesn’t seed in UK.

Where? Along railways, disturbed ground, woodland. High range of tolerances, can push through concrete. Partial die back in winter to stems.

Why? Introduced as an ornamental plant in 1850, for sale from Kew Gardens!

Management advice

•Specialist contractors

•Targeted herbicide

•Controlled waste landfill

•Do not compost

Report sightings?

Yes, it is very widespread and high economic impact by damage to homes and infrastructure.

Water fern

Azolla filiculoides

When? Dies back in winter, but grows vigorously in summer.

Where? slow and standing freshwater; ponds, reservoirs, canals. Forms 30cm deep mats, blocking all light to water column.

Why? Dispersed by birds, boats, spores and machinery, is native to the US. Can exploit poor water quality, fragments easily, and causes 'dead zones' beneath dense mats.

Management advice

•Scooping off mats

•Kill before composting

•Spraying with herbicide

Report sightings?

Yes, it is very widespread and high economic and ecological impact.

false - Laura Cronin

Rhododendron (ponticum)

R. ponticum and hybrids

When? Evergreen, but flowers from May onwards – spreads by prolific seeds and also vegetative.

Where? Woodlands, takes over understory.

Why? Introduced from Mediterranean in 18th Century, an escapee of private gardens. It causes acidification of soil and replaces diverse understory with dead zones.

Management advice

•Injecting herbicide into stumps

•Cutting back regularly to stumps

•Wear gloves

Report sightings?

Not required, it is very widespread and low economic impact and likely to naturalise.

Australian stonecrop / NZ Pygmyweed

Crassula helmsii

When? Dies back in winter, but grows vigorously in summer.

Where? Covers pond banks canals and reservoirs, outcompeting other native vegetation.

Why? Brought from Tazmania in 1911 as an oxygenating pond plant, spreading by birds, boats, mechanical means. First recorded in wild in 1951. More of an active issue in Avon than water fern.

Management

•Scooping off mats in winter

•Cover to kill

•Kill before composting

•Spraying with herbicide

Report sightings?

Yes, it is very widespread and high economic and ecological impact.

Three cornered leek/ 3c garlic

Allium triquetrum

When? Is an early spring arrival, appearing in February and dying back around April

Where? Wherever it is planted! hedgerows, verges, woodlands

Why? Introduced from Mediterranean in 18th Century, likely as a food source

Management advice

•Pulling up bulbs

•Cutting back

•Edible! And tasty

Report sightings?

Not required, it is very widespread and low economic impact, likely to naturalise.

Virginia creepers – Parthenocisis sp.

P. inserta and P. Quinquefolia

When? Main growing season June – October, flowers (barely) in midsummer.

Where? A vigorous climber, usually cladding houses and fences, will cloak wild scrub and trees. Spread by bird droppings.

Why? Introduced for ornamental reasons (from the US) in 1629, but recorded wild 1920's.

Management

•Cutting back

•Uprooting

•Irritant sap, wear gloves

Report sightings?

Not required, it is very widespread and low economic impact

Resources

National Lottery Heritage Fund

Advice given by the Team Wilder Community Ecologist, was made possible with the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

(C) Hannah Bunn

Be part of Team Wilder

All actions for nature collectively add up and creates life for people and wildlife.

Share your actions for nature to inspire and motivate others.

Talk about what you do to make these actions part of everyday life.

Share and tag us on @avonwt on social media as well.

Log your actions for nature on the map